Agents of Socioeconomic Mobility: How Dallas College Students Reshape Family Trajectories

Sayeeda Jamilah

Insight Brief - Published October 22, 2025

Introduction

Education is often framed as a ladder for socioeconomic mobility, but for many underserved families, the steps are fragile or completely missing. Dallas College, like many community colleges, is uniquely positioned to build a ladder for a broader range of student populations through flexible entry points to postsecondary education, affordable tuition, and stackable credentials in high demand fields, allowing students to build career skills progressively. Research demonstrates that higher education not only transforms the lives of individuals but can also have a ripple effect on the lives of their children, siblings, and extended families. Household income and college completion are key factors in predicting upward mobility, and community colleges serve as facilitators of this socioeconomic advancement by providing academic, social, and financial supports to ensure persistence and completion, especially for low-income students (Creusere et al., 2019; Chetty et al., 2017; Perna & Jones, 2013). While supportive postsecondary institutional structures committed to students’ needs help them access and complete credentials, student success is still largely influenced by personal factors—specific choices, behaviors, assets, and personal strengths—and these variables drive upward mobility for students and their families. In the Research Institute’s exploration of Dallas College’s impact on socioeconomic mobility within the community and its lasting influence on families, qualitative insights from interviews with seven students highlight that the emergence of a college-going culture and pursuit for a better life often begins with a single individual’s determination to overcome social barriers, gain social capital and educational assets, model perseverance and resilience, and transmit aspirations within one’s family. In a series of interviews conducted by the Research Institute, these students, who span a mix of ages and programs of study, exemplified the myriad ways that Dallas College students and their families navigate systems of higher education and ultimately achieve success (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Profiles of Interviewed Students

Adult learners and student parents entering or returning to postsecondary education frequently encounter complex barriers that hinder their academic success. Balancing work obligations, caregiving responsibilities, and coursework demands often result in persistent time poverty and stress, and limited financial resources, inadequate access to affordable childcare, and inflexible institutional structures (e.g., limited evening/weekend and online course options, rigid academic calendars, strict attendance policies) further intensify these challenges. Such obstacles contribute to disparities in educational outcomes among this nontraditional student population, particularly for first generation students who have limited cultural capital to navigate the higher education environment (White et al., 2020). Many have either attended college or aspired to earn a degree or credential, but uncertainty about their academic or career paths and doubts about their abilities often discourage them from completing their studies or even beginning their postsecondary education (Gault et al., 2020; Tuset, 2022). Nationally, approximately half of adult learners complete a postsecondary credential within six years compared to over two-thirds of traditionally aged students (Lee & Shapiro, 2023), and the gap is larger among student parents, of whom approximately 18% earn an associate or bachelor’s degree within six years of entering postsecondary (Cruse er al., 2021). Examining the success stories of this student group provides insight into the factors that enable them to overcome obstacles and sustain their motivation in the pursuit of their educational goals.

Student Behaviors and Characteristics Propel Mobility

The narratives of college-going within families coupled with diverse interpretations of socioeconomic mobility illustrate the individualized ways in which students envision and pursue the American Dream.

For students living on the verge of poverty, the urgency to improve their financial circumstances often propelled them into postsecondary education, and their drive to secure economic stability for their families sustained their persistence despite obstacles. When thrust into the role of sole provider for her daughters, husband, and mother, Angie, who did not complete high school, unearthed her childhood aspirations of becoming a teacher, endured several challenging years in ESL coursework at Dallas College, and adapted to the cultural expectations of the college classroom until she eventually earned an AAS in Teaching while juggling multiple jobs and caregiving responsibilities. Fortuitously learning about dual credit opportunities from a conversation between customers at her workplace, she persuaded her daughters to enroll in courses at Dallas College during high school, enabling both to earn associate degrees. Today, her daughters hold master’s degrees and have established successful careers in secondary and higher education, and Angie has secured a fulfilling and well-paying role as a Special Education Teaching Assistant and aspires to continue her academic journey to earn a bachelor’s degree.

"I wasn’t ready for college…but I went to Richland myself and signed up for continuing education ESL classes. I finished those classes in two years, and then it took three years to get my associate…and I was working three jobs. I cried the whole time…I couldn’t do my homework, but then I put myself to do it because I was always telling myself ‘you have two kids…you want your kids to go to school? You want your kids to finish college?’" – Angie, AA in Teaching, 49

Carmen’s journey toward upward mobility is defined by her resilience and dedication to seeking knowledge and opportunities to reshape her daughter’s future. A university graduate from Mexico, she left a life of comfort for the U.S., where she experienced martial challenges and economic hardship after divorce. Carmen went to great lengths to foster a college-going mindset in her daughter, whose father discouraged her from pursuing higher education, and enrolled her in a mentorship program through Big Brothers Big Sisters where she had the chance to visit colleges across the country. She stayed informed about higher education and guided her daughter to start at Dallas College before transferring to a four-year university. Realizing her own degree held little value in the U.S., she joined her daughter in an accounting certificate program and took one class per semester. Even after losing their home in a tornado and pausing their education to rebuild, Carmen resumed her studies at Dallas College one year later, while her daughter continues in a doctoral program; despite the hardships, Carmen sees her sacrifices as worthwhile in building a better future in the U.S.

The pursuit of a better life is multifaceted, and the stories of progress do not always follow a linear path from poverty to financial stability. Two alumnae adapted to unforeseen circumstances that interrupted their college plans and remained steadfast in their educational goals. For Denise and Jennifer, college was a family norm and a personal expectation, until an unplanned pregnancy and the sudden loss of a parent forced both women to leave university and return to their family homes. Jennifer cautiously navigated career ambitions with the demands of parenthood, opting to complete a more manageable AA in Communications over the rigorous AAS in Nursing, and later advanced her career by completing Data Science training at a four-year institution. Although she did not follow her family’s tradition of earning a four-year degree or beyond, Jennifer believes her career in a high-demand field has led to greater financial success than her parents realized; her son, who participates in dual credit, plans to attend a four-year college after high school.

“…I took a different type of path…[I] didn’t graduate with traditional university degree…but I would say [I’m] doing better financially than my parents because of the professions [I’m] in…college can change lives in many ways, and you don’t always have to take the traditional path. ” – Jennifer, AA in Communications, 37

After the loss of her mother, Denise took the role of guardian to her younger brother, a responsibility she has embraced without allowing it to deter her ambition of becoming a mechanical engineer. Her late mother held a bachelor’s degree in human resources and instilled a strong college-going ethos in their home. Having completed an AS degree at Dallas College, Denise is employed with a good salary in a tech laboratory and plans to transfer to a local university to complete her engineering studies once she has saved enough to continue. Her brother, a junior in high school, is considering enrolling at Dallas College after graduation.

“My brother wants to emulate my path in life, and I have to remind him he’ll have his own.” – Denise, AS, 27

The journey to postsecondary education for some student parents may not have come to fruition were it not for the academic drive and college aspirations demonstrated by their children. The influence of youth actively engaging in dual credit programs and planning for higher education—role modeling educational ambition for their parents—emerged as a powerful and recurring theme in the intergenerational mobility narratives of Dallas College families. After years of working as a bookkeeper in a family business—skills she acquired through hands-on experience—Amanda’s daughter, a Dallas College student at the time, encouraged her to give college a chance. She enrolled in the AAS program in Business Administration and expects to graduate within the next year, with plans to seek employment at a larger company. Frederick immigrated to the U.S. from El Salvador with his parents as a child, and the family settled in a small town west of the DFW metroplex. He and his wife had no plans to pursue education beyond high school, but they held strong aspirations for their children’s academic and professional success. Inspired by his son’s dual credit experience at Dallas College where his peers were gaining skills in welding, construction, and electronics, Frederick felt encouraged to pursue a credential in Construction to advance in his career. His son now attends a local university, and he is a lead foreman with an AAS degree and plans to transition into a management role.

"I did not like school and couldn’t see myself getting to that level of education. My son encouraged me...I was out of school for so long, it was hard to feel motivated. But I wanted to prove to my son and daughter that I could do it." – Frederick, AAS in Construction, 39

Rochelle, a 52-year-old single mother, spent most of her adulthood making ends meet through jobs in the service industry and now works in medical billing. She carried forward her mother’s strong emphasis on education, instilling that value in her children, even though her own educational journey was limited. While she did not finish cosmetology school after high school, her daughter’s participation in Dallas College’s Promise program reignited her own educational ambitions. Rochelle discovered the Parent Promise initiative by chance at a career fair in her daughter’s school district and credits it for helping her return to college to pursue a medical coder certificate. Her daughter plans to pursue a bachelor’s degree in social work.

“I just needed a change. I needed to be able to pay all my bills and still have some money, and working retail jobs wasn’t doing it for me. I didn’t want to be a statistic…I wanted to make sure I had a sound future for myself, not just for me, but for my kids.” – Rochelle, Parent Promise Student in AAS pathway, 52

A belief in higher education as a means to upward mobility is exhibited in these examples as two-way intergenerational exchanges—from parents to children and children to parents—centering education as a family value. Resilience, adaptability, perseverance, and the ability to serve as role models are intrinsic qualities our students embody, and these characteristics empower them to transform challenges into opportunities.

Institutional Supports & Opportunities to Strengthen Socioeconomic Mobility Pathways

Students’ perceptions suggest that Dallas College has been both a stepping-stone for ambitions of a four-year degree and above and a destination for career-ready credentials. The College’s affordability, flexibility, and targeted supports have made it possible for students to persist (Figure 2). The interviews revealed that the financial practicality and proximal convenience of the College’s campuses were key factors that influenced students to enroll despite their educational backgrounds or family circumstances. Some students expressed a strong affinity and emotional connection to the campus where they began their studies or completed the majority of their coursework, and many highlighted the quality and impact of their instructors as imperative to their academic success. Angie emphasized how her Dallas College mentors in the ESL program encouraged her to continue on a degree pathway; Jennifer shared that her Dallas College advisor made it easy to transfer the dual credit courses she completed in high school into her associate degree program to help her stay on track academically after transitioning from her four-year institution; and Rochelle described the Parent Promise program as transformative and a “great blessing” during a period of financial hardship for her and her children.

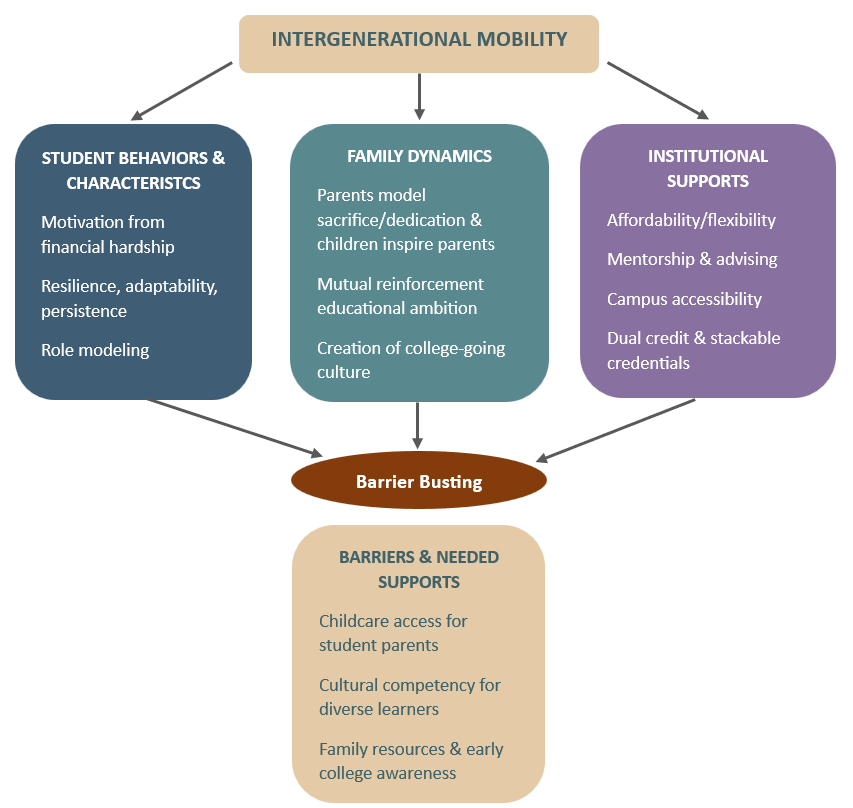

Figure 2. Components of Intergenerational Mobility

However, students emphasized the importance of expanding flexible childcare options across all campuses, particularly those in urban areas to provide support for student parents. Jennifer reflected on the difficulty of finding childcare during her nursing clinicals, which left her feeling alone in her college journey as a student parent. Students also encouraged greater cultural competency among Dallas College faculty, especially in engaging and instructing students with limited English proficiency; Angie conveyed that certain instructors failed to understand her insecurities in the classroom and the challenges she faced in completing assignments, which left her without the support she needed to fully engage. Several interviewees recommended that Dallas College invest in initiatives such as campus visits, community outreach, and targeted enrichment programs to cultivate early college awareness and aspirations among middle and high school students throughout the Dallas area. Carmen shared that many parents do not possess the awareness and resources to prepare their children for college early on; she hopes that the College can assume a more proactive role in guiding families, particularly those with limited access to information, by offering enrichment opportunities and knowledge support, so that parents are not left to navigate the postsecondary landscape alone.

Conclusion

The stories of Dallas College students and their families illustrate that socioeconomic mobility is not achieved through a single pathway, but by way of a complex dynamic between individual resilience, family support, and institutional support. Students’ persistence through challenges demonstrates how personal determination, when coupled with the right educational opportunities, can transform both individual lives and entire family trajectories. Just as the parents in our study model sacrifice and perseverance for their children, children also spark aspirations in their parents, creating a cycle of mutual encouragement that upholds intergenerational advancement. By showcasing the voices of students, this brief underscores that Dallas College is not only a vehicle of opportunity but also a catalyst for upward mobility, though students themselves remain the drivers of their educational and socioeconomic success.

Note: Names of students and alumni have been aliased in adherence with IRB protocol.

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., Saez, E., Turner, N., & Yagan, D. (2017). Mobility report cards: The role of colleges in intergenerational mobility (No. w23618). National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23618/w23618.pdf

Creusere, M., Zhao, H., Bond Huie, S., & Troutman, D. R. (2019). Postsecondary education impact on intergenerational income mobility: Differences by completion status, gender, race/ethnicity, and type of major. The Journal of Higher Education, 90(6), 915-939. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2019.1565882

Cruse, L. R., Richburg-Hayes, L., Hare, A., and Contreras-Mendez, S. (2021). Evaluating the role of campus child care in student parent success: Challenges and opportunities for rigorous study. Institute for Women’s Policy Research. https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Evaluating-the-Role-of-Campus-Child-Care_FINAL.pdf

Gault, B., Holtzman, T., & Reichlin Cruse, L. (2020). Understanding the student parent experience: The need for improved data collection on parent status in higher education (Briefing Paper No. C485). Institute for Women's Policy Research. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED612522.pdf

Jones, A., & Perna, L. (2013). The state of college access and completion: Improving college success for students from underrepresented groups. In B. T. Long & A. Boatman (Eds.), The role of remedial and developmental courses in access and persistence (pp. 1-24). New York: Routledge Books. https://www.routledge.com/The-State-of-College-Access-and-Completion-Improving-College-Success-for-Students-from-Underrepresented-Groups/Perna-Jones/p/book/9780415660464

Lee, S., & Shapiro, D. (2023). Completing college: National and state reports with longitudinal data dashboard on six-and eight-year completion rates (Signature Report No. 22). National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Completions_Report_2023.pdf

Tuset, M. (2022, November 7). Overcoming barriers for adult learners. Council for Adult and Experiential Learning. https://www.cael.org/resouces/pathways-blog/overcoming-barriers-for-adult-learners

White, J. W., Pascale, A., & Aragon, S. (2020). Collegiate cultural capital and integration into the college community. College Student Affairs Journal, 38(1), 34-52. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1255551.pdf